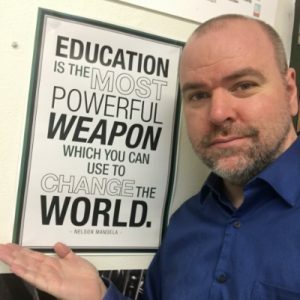

Better Scholarly Writing.

Our PhD trained writing teachers support all aspects of academic writing projects from idea development, to writing and revision, to publication. We focus on developing sustainable writing habits and writing project management systems to support an academic career from graduate school through university leadership. You don’t need a writing coach; you need a writing teacher.